In the modern world, late-night schedules have become the norm for many. Surveys show that people in industrialized countries now sleep only about 6.8 hours per night on average – roughly 1.5 hours less than a century ago. Yet adults biologically need around 7–8 hours of sleep nightly for full health. This chronic sleep restriction has grown worse over recent decades due to lifestyle changes. The spread of electric lighting, 24/7 technology, and round-the-clock work and entertainment means artificial light now extends our “day” well past sunset. As a result, people stay up later and often get too little rest. Experts note that this widespread “sleep debt” is more a product of social and economic shifts – from artificial light to screen addiction – than any change in human biology.

Over time, a steady pattern of late nights can set up a cascade of health problems. To understand why, it helps to know about the body’s internal clock, the circadian rhythm, which normally runs on a 24-hour cycle synced to light and dark. This clock controls sleep-wake patterns and coordinates many physiological functions – including critical liver tasks – in daily cycles.

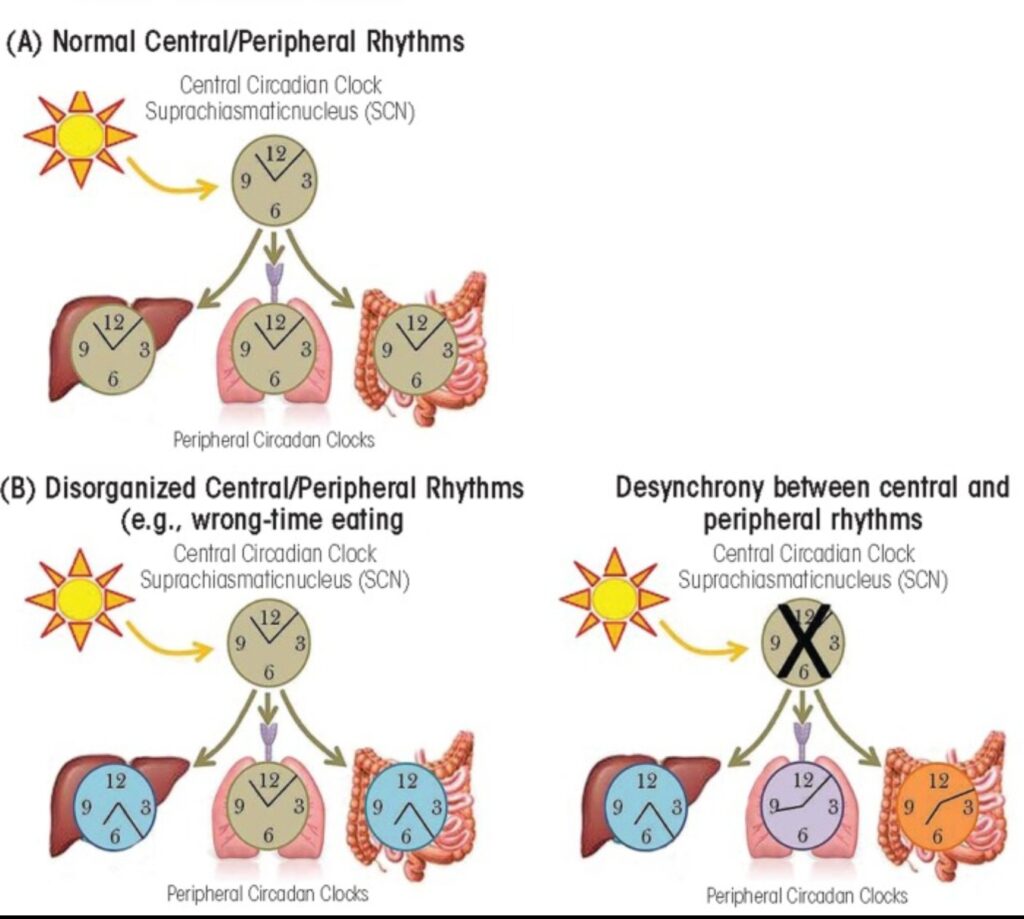

The central circadian clock in the brain (SCN) is normally synchronized by daylight and in turn regulates “peripheral” clocks in organs like the liver and gut. Staying up late or eating at the “wrong” time can decouple these clocks (B), disrupting normal metabolism and detoxification.

Under healthy conditions, the brain’s master clock (the suprachiasmatic nucleus, SCN) is reset each day by exposure to sunlight, and it keeps peripheral clocks in organs on time. This coordination ensures that sleep, hormone release, digestion, and detox activities occur at the optimal time of day. For example, certain immune cells and hormones peak during sleep, while others are active during wakefulness. Likewise, the liver – our main detox and metabolic organ – ramps up processing when it expects nutrients and wind-down/repair at night. In general, organisms use circadian rhythms to anticipate daily changes and adjust physiology accordingly.

When we stay up late or work nights, this alignment breaks down. The SCN can become uncoupled from its normal light cue, and “peripheral” clocks in the liver or gut no longer match the day-night cycle. Even a few nights of disorganized schedules can reset liver genes. In one study, prolonged sleep deprivation in animals induced a major reprogramming of the liver’s daily gene expression. Researchers found that genes involved in carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism became more active during abnormal “awake” periods. In other words, the sleep-deprived liver shifted into emergency mode to supply energy. Over the long run, this constant overdrive can exhaust the system.

Moreover, staying up late suppresses natural hormone signals that normally protect the liver. Melatonin, the hormone of darkness, is a powerful antioxidant made at night by the pineal gland. Beyond helping us fall asleep, melatonin has been shown to guard the liver against injury and inflammation. (Studies of liver disease find that melatonin scavenges free radicals, calms inflammation, and even slows fibrosis and fatty buildup.) But artificial light and late-night habits keep melatonin low. That means you miss out on melatonin’s anti-inflammatory, detoxifying influence on the liver.

All of this adds up to real damage in the long term. Epidemiological studies now link habitual late bedtimes and other poor sleep behaviors with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) – a buildup of fat in the liver not due to alcohol. For example, a recent large survey found that people who went to bed late were significantly more likely to have fatty liver; conversely, those who modestly improved sleep quality saw about a 29% reduction in NAFLD risk. Scientists suspect the disrupted circadian and hormonal environment of chronic late nights helps drive the liver to store fat rather than burn it. In short, what you do at night profoundly affects the liver’s nightly job of detox, repair and metabolic regulation.

Mental and Emotional Health Effects

The harm from late nights isn’t confined to the liver. Your brain and mood are also deeply affected by chronic sleep loss. Most people recognize this from experience: a poor night’s sleep often leaves you irritable, foggy and more prone to stress. Research confirms this link. For instance, when people lose sleep they exhibit much stronger negative emotional reactions to relatively minor stressors. Brain studies show that parts of the emotional-regulation circuitry stay hyperactive after sleep deprivation, so you can’t process situations calmly.

Over longer periods, the consequences are more serious. Persistent insomnia or sleeping only a few hours per night is associated with much higher rates of depression and anxiety. In one survey, individuals with chronically short sleep were far more likely to report symptoms of depression, anxiety or even suicidal thoughts than those getting adequate rest. Part of this is thought to be due to missing REM sleep, which is crucial for processing emotional memories and stress. Sleep researchers note that insufficient REM (often a consequence of late or disturbed sleep) makes it harder to consolidate positive experiences and regulate negative feelings.

In fact, normal sleep seems to be essential for building mental resilience. One experiment had participants get vaccinated and then either sleep or stay awake. Those who slept on the night after the vaccine developed a much stronger immune response – a sign that their brains effectively “remembered” and processed the vaccine antigens during sleep. Conversely, skipping sleep after immune challenges generally produces weaker responses and more vulnerability. By similar logic, if you chronically skip sleep, your brain’s ability to recover from emotional and cognitive stress may weaken over time, making mood disorders and cognitive decline more likely.

Hormonal and Metabolic Consequences

Sleep serves as an important regulator of our hormones and metabolism. When you stay up late, this balance is upset in several ways. First, sleep loss skews appetite hormones. Research shows that even a single night without sleep raises the hunger hormone ghrelin while lowering leptin, the hormone that signals fullness. This hormonal shift tells your body it’s starving, even if you’ve eaten enough. Indeed, sleep-deprived people report feeling less satisfied after meals and tend to eat more calories the next day. In one controlled study, volunteers restricted to 5 hours’ sleep per night for four nights showed higher insulin levels after a meal and faster clearance of fats into fat tissue – changes that predispose to weight gain. Over a lifetime, this can translate to significantly higher obesity and diabetes risk.

Short sleep also directly impairs glucose regulation. Hormones like insulin and cortisol are normally tuned by the circadian clock: insulin sensitivity is higher during the day, cortisol normally drops at night, and growth hormone peaks during deep sleep. Breaking that pattern (for example, by being awake late and exposed to light) leads to insulin resistance and elevated nighttime cortisol. Studies find that sleep-deprived people tend to have higher blood sugar levels after meals and a greater risk of type 2 diabetes. In population studies, insufficient sleep is consistently linked to metabolic syndrome: those sleeping fewer than 6–7 hours per night have higher odds of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes. In practice, this means that a habit of late nights often goes hand-in-hand with weight gain, prediabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

Immune System Impairment

Another hidden victim of late-night habits is the immune system. During sleep, our bodies carry out important immune “housekeeping” – distributing cells, fighting infections and building memory of pathogens. Strong evidence shows that when you miss sleep, immune defenses suffer. For instance, experiments comparing normal sleep vs. total sleep deprivation found that sleep encourages movement of T cells into lymph nodes (where immune responses are coordinated) and boosts the production of helpful cytokines like interleukin-12. In practical terms, one study showed that getting a good night’s sleep after vaccination greatly increased the number of vaccine-specific immune cells and antibodies, whereas staying awake reduced that response.

In contrast, chronic sleep loss produces a pro-inflammatory state and undermines immunity. A review by sleep scientists concluded that “prolonged sleep loss” has detrimental effects on immune function, showing that loss of sleep raises inflammatory markers and disrupts immune cell activity. People who habitually sleep too little are more prone to infections like colds, and their bodies do a worse job of remembering those infections. In concrete terms, studies have linked short or disrupted sleep with higher incidence of things like the common cold or slowed recovery from illness. Over years, the low-grade inflammation associated with chronic poor sleep may also contribute to diseases such as arthritis or autoimmune disorders. In short, regularly depriving yourself of nighttime rest is like undermining your body’s own medicine cabinet – you lose the immune boost that healthy sleep provides.

Cardiovascular and Long-Term Disease Risk

Chronic late nights also strain the heart and blood vessels. Numerous studies have now connected short or inconsistent sleep with higher rates of heart disease, hypertension, and stroke. One review of the literature notes that sleep deprivation is epidemiologically linked to elevated blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and even diabetes. Large surveys support this: for example, a U.S. poll found only about 37% of adults get 8 hours nightly, and individuals sleeping 6 hours or less had much higher rates of hypertension and heart attacks. Another analysis of mortality data showed a clear U-shaped curve: men sleeping ≤6 hours per night had roughly 1.7 times the death rate of those sleeping 7–8 hours, and those sleeping ≥9 hours also showed elevated mortality. Although extremely long sleep also carries risks, the key point is that habitual short sleep dramatically raises risk.

Mechanistically, lack of sleep increases sympathetic (“fight or flight”) activity and inflammation. You literally stay a bit “revved up” when you don’t rest, so your body pumps more stress hormones (like cortisol and adrenaline) and your arteries remain tense. Over time this drives up blood pressure and can injure arterial walls. For example, UCLA health experts note that night-shift workers (who routinely disturb their circadian rhythm) have higher rates of hypertension, heart attack and stroke. Irregular sleep also disrupts hormonal balances like renin-angiotensin (involved in blood pressure), further raising cardiovascular risk.

In addition, chronic sleep disruption is associated with other long-term problems. One concern is cancer: the World Health Organization has classified “night shift work that disrupts circadian rhythm” as probably carcinogenic. Evidence suggests a plausible mechanism: melatonin normally helps suppress tumors, and disrupted sleep allows cancer cells to grow unchecked. A UCLA report notes that circadian misalignment interferes with DNA repair and cell-cycle regulation – meaning an off-balance clock can allow more DNA damage to accumulate and tumors to escape suppression. So, in the long run, the habit of late nights may modestly elevate risks for some cancers.

Overall, then, chronic insufficient sleep and late bedtimes have been linked to a broad range of diseases – from obesity and diabetes to heart disease and certain cancers. Many studies conclude that people who consistently get too little sleep (or who routinely shift their sleep schedule) suffer higher rates of age-related illnesses and even higher mortality. In practice, that means each hour of sleep you lose is an investment not made in your long-term health.

Why We Stay Up Late: Lifestyle and Technology

What drives people to stay up late despite the risks? Much of it is modern lifestyle. Bright electric lights, cellphones, computers and TVs make it easy to ignore bedtime. Blue-wavelength light from these devices is particularly disruptive to circadian rhythms and melatonin production. Even dim artificial light in the evening (around 8 lux) can suppress melatonin release and signal “daytime” to the brain. Several studies have shown that exposure to blue light at night (from tablets, phones, LED bulbs, etc.) delays the body clock by hours. For example, in a lab experiment, 6.5 hours of blue light in the evening suppressed melatonin nearly twice as much as green light and shifted circadian timing by about 3 hours. In real life, the result is that streaming shows or scrolling social feeds makes your brain feel alert at bedtime – precisely when it should be winding down. Sleep experts warn that keeping bright screens on in the hours before bed will throw the circadian rhythm “out of whack” and contribute to insomnia.

Social media and FOMO (“fear of missing out”) also fuel late nights. Surveys show that a large majority of young people use social apps at bedtime. In one poll, about 70% of hospital workers and university students reported checking social media after getting into bed. Nearly half of Generation Z even admit to losing sleep regularly because of TikTok or similar sites. The endless stream of news, updates and connections keeps people glued to screens late into the night. This compulsive checking is driven by FOMO – the anxiety that if you log off, you’ll miss something important happening online. People with high FOMO tend to check their phones within minutes of trying to sleep, significantly fragmenting their rest. In short, technology and social habits now actively push us to sacrifice sleep for engagement.

Outside of tech, other factors can force late nights. Shift work is a prime example: nurses, factory workers, emergency personnel and others who work nights or rotating schedules essentially trade their day for night. Long-term studies of shift workers reveal higher incidence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. When your work schedule makes you nocturnal, your circadian clock is constantly misaligned to society and the sun. Even apart from jobs, modern 24/7 culture (late-night stores, around-the-clock schedules) erodes the traditional “early to bed” pattern. Finally, some people are naturally “night owls” by temperament, but when these preferences run counter to work or school schedules, chronic “social jetlag” sets in.

In combination, all these environmental factors – screens and blue light, social pressures, irregular work hours, nightlife and caffeine – create a powerful push toward late bedtimes. Many of them (like screen use) directly interfere with the same melatonin and light signals needed for healthy sleep. The result is that late nights have become self-reinforcing in our society, even though biology clearly pays a price.

Long-Term Risks of Chronic Late Nights

The net effect of all these acute problems is serious when compounded over years. Research finds that people who are “evening types” or who consistently delay sleep have higher risks of chronic illness. For example, one Finnish cohort study found that habitual night owls had higher rates of all-cause mortality decades later, even after controlling for other factors. In general, studies like the Alameda County Study have shown that sleeping consistently less than 6–7 hours per night is associated with a significantly higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke and other causes.

Similarly, the repeated disruption of sleep leads to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Over time this inflammation is linked to diabetes, atherosclerosis and even neurodegeneration. Preliminary evidence suggests that longstanding sleep loss may accelerate cognitive aging: in older adults, chronic insomnia has been associated with faster declines in memory and brain volume. Another potential concern is that sleep helps clear amyloid proteins from the brain, so long-term sleep deficiency could theoretically raise Alzheimer’s risk. (Indeed, very short sleep has been associated with higher levels of certain Alzheimer’s-related proteins in cerebrospinal fluid.) While these links are still under study, they raise a worrisome possibility: consistently skimping on sleep could potentially contribute to earlier dementia risk.

The bottom line is that chronic late-night habits, like smoking or poor diet, are a predictor of long-term poor health. Each night’s lost sleep is like a missed mortgage payment on wellness: you may not see the damage immediately, but over the years it accumulates. Numerous health agencies now emphasize that adequate, regular sleep is as important a health behavior as exercise or diet. Given the growing evidence of the harm, many experts consider insufficient sleep a public health issue.

Tips for Better Sleep Hygiene

Improving your sleep habits can help reverse these risks. The goal is to align your schedule with your natural circadian rhythm and minimize the factors that push bedtime later. Some practical tips include:

- Keep a consistent schedule. Go to bed and wake up at roughly the same times every day – even on weekends. Consistency reinforces your internal clock, making it easier to fall asleep at night and wake up refreshed in the morning. Aim to allow yourself enough time (7–8 hours) each night to meet your sleep needs.

- Establish a relaxing bedtime routine. Spend the last 30–60 minutes before bed winding down in a calm way. Take a warm bath or shower, do gentle stretching or meditation, or read a book. Avoid stressful or stimulating activities (arguments, work emails, intense exercise) right before bed. A fixed routine signals to your body that it’s time to sleep.

- Eliminate bright screens before sleep. Turn off TVs, computers, tablets and phones at least 1–2 hours before bedtime. The blue light from these devices suppresses melatonin and tricks your brain into thinking it’s still daytime. Instead, use dim lighting or red-hued bulbs in the evening, as red light has much less impact on circadian rhythms. Some people also find blue-blocking glasses useful if they must use screens at night.

- Optimize your sleep environment. Make your bedroom quiet, dark and cool. Use blackout curtains or an eye mask to block light, and earplugs or a sound machine to muffle noise. A cool room (around 60–67°F, 15–19°C) is ideal for most people’s sleep. Reserve your bed for sleep (and intimacy) only, not for work or entertainment, to strengthen the mental association.

- Get morning sunlight. Natural light exposure first thing in the morning helps reset your circadian clock daily. Try to spend time outside or near a window with bright light soon after waking. Daytime light boosts alertness when you need it and enhances the drive for sleep at night.

- Limit caffeine and heavy meals in the evening. Caffeine can stay in your system for 6–8 hours, so avoid coffee or energy drinks after mid-afternoon. Alcohol may make you sleepy initially but fragments deep sleep, so don’t rely on it. Also avoid large or spicy meals close to bedtime; digestion can keep your body active.

- Exercise regularly, but not too late. Physical activity can improve sleep, as long as it’s done early enough. Aim for moderate exercise during the day or early evening. Vigorous workouts within an hour of bedtime can raise body temperature and delay sleep onset.

- Be mindful of naps. Short “power naps” (20–30 minutes) can be refreshing, but long or late afternoon naps can make it harder to fall asleep at night, especially if you already struggle with sleep.

- Manage stress. Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing, meditation or journaling to clear your mind before bed. Anxiety and racing thoughts often fuel insomnia, so tackling worries earlier in the day (or setting aside “worry time”) can help.

- Consider professional help if needed. If chronic insomnia or sleep problems persist despite good habits, consult a healthcare provider. They can check for underlying sleep disorders (like sleep apnea or restless legs) and suggest therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, which have strong evidence of benefit.

By adopting these sleep hygiene practices and aligning your habits to the body’s natural rhythm, you can make those late nights far less tempting – and enjoy much better health and energy in the long run.

In sum, while staying up late occasionally isn’t a catastrophe, a persistent pattern of late nights disrupts nearly every bodily system. It thwarts the circadian orchestration of hormones, metabolism, immunity and regeneration. Over time, this increases the chance of serious health problems from fatty liver and obesity to depression and heart disease. In contrast, giving your body the sleep it needs each night is one of the simplest and most powerful ways to protect your liver (and whole body), sharpen your mind, balance your hormones, and strengthen your heart.